After DEV by Martin Wallis

After graduation I went to work on a farm in France to improve my French. My linguistic skills were sternly put to the test when my employer invited me to join him (and about 10,000 incandescent sheep farmers) in Rodez to protest at British imports of NZ lamb. For reasons best known to himself, my companion pointed at me and shouted “C’est un Anglais!!!”. Which caused a surge of protestors in my direction – “Dehors L’Albion Perfide!!!”. I held up my hand for silence, then told them at length in faultless accent du Midi that my companion was marteau (nuts). He, in turn, looked sheepish.

In 1980 I went to Africa, to the World Bank Livestock Development project at Marial Bai, Wau,

Bahr-el-Ghazal training the Dinka to ‘teach their oxen to dance’. From southern Sudan I went in 1982 to Burundi where I managed a couple of fermes pilotes up-country, among other things training the Watutsi long-horn cattle to perform fieldwork and to test prototype tool carriers (made in the project workshop in Bujumbura by ex-DEViants Adrian Friggens and Dr David Barton).

From Burundi I moved in 1984 to Tanzania – Mbuba village in Ngara, Kagera This verdant, bucolic and sleepy village was – ten years later – transformed almost overnight into a teeming transit centre and triage hub for the hundreds of thousands of Rwandan refugees who flooded across the Rwandan/Tanzanian border to escape the mayhem that descended upon Rwanda in the 1994 genocide.

In Gitega (Burundi) there is a monument to commemorate the deaths in 1993 of 75 Tutsi schoolboys murdered during interethnic bloodletting: the monument bears the invocation, writ large ‘Plus jamais ça” (Never again). Fine words butter no parsnips.

From Tanzania to Uganda, in the throes of civil war to oust Milton Obote. My infelicitous introduction to Uganda was to be held up at gunpoint, the muzzle of an AK47 rammed into my left ear, by a bunch of heavily armed ‘bandits’ on the road from the airport at Entebbe to Kampala. Fortunately I’d had previous experience of this sort of thing in both southern Sudan and Burundi. “Give me money give me whiskey” the gunman said. I shot (no pun intended) a sideways glance at my driver. He had turned to stone and was drenched in sweat. I removed the gun from my ear and lowered the barrel, saying in (awful) Juba Arabic that I had no money or whiskey, but that the next time we met I would surely see to it that he would get what he deserved. The element of surprise – he didn’t understand a word, and stepped back – was enough for me to seize the initiative and nudge my hapless driver to drive on. And off we tootled poli poli.

Perhaps DEV – the School of Global Development – might consider running a ‘what to do if you get into a mucky fuddle at a roadside checkpoint’ short course for graduates: the ‘Don’t Panic’ seminar – https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=rjxseHuUSYI The rest of my stay in Uganda was rather less eventful until the penultimate day before my departure when I had a serious RTA which effectively ended my career in Africa.

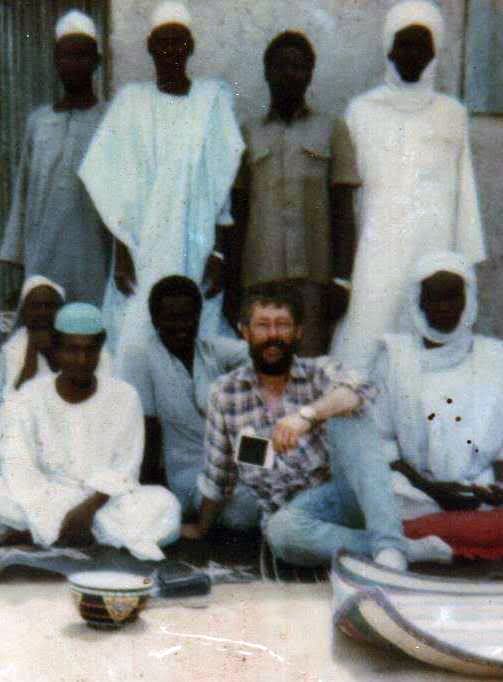

I did have one ‘last hurrah’, doing ‘multidisciplinary’ field research in 1989/90 for Oxfam in Chad (Kanem and Lac Prefectures). I did some preliminary desk research, and one article in particular caught my eye – https://www.jstor.org/stable/23076624 – “Bien des Tchadiens considèrent que le système tributaire prévalant au Kanem est le plus abusif qui ait vu le jour dans les régions musulmanes de leur pays” (Many Chadians feel strongly that the system of tribute in force in the Kanem is the most inequitable that has ever seen the light of day in the Muslim regions of their country). When I set foot in Kanem/Lac it didn’t take me too long to work out that “ le système tributaire” was indeed the crux of the issue. When I arrived at my up-country base in Mao, I was instantly besieged with requests for ‘moto-pompes‘ (for ouadi irrigation) and livestock to reconstitute lost herds of goats, cattle and camels… pleas not from destitute herders or agropastoralists who had lost all as a result of a sequence of years of extreme drought… but from half-adozen gentlemen rocking up outside my humble abode in very top-of-the-range véhicules toutterrain (4x4s). I sent for tea, glasses and a sugar loaf, We had a polite but ‘frank exchange of views’ after which they left empty-handed.

Over the following months I criss-crossed Kanem/Lac prefectures interviewing farmers and herders, knowing that ultimately it was the Sultan of Kanem – Ali Zezerti – who had the last word and who would ‘appropriate’ any benefits accruing to his tributaires. I wrote my report for Oxfam. Did I change anything, did I move the hand on the dial? No. I’d love to be able to say that this https://reliefweb.int/report/chad/village-gurus-training-mothers-tackle-hunger-chad was the fruit of my labours but it was not. Though I do remember with pleasure the many times that I was their guest in Kékédina.

Back in Blighty I decided that I was no longer either mentally or physically fit enough to do fieldwork. So, with heavy heart, I ‘retired hurt’ and spent the rest of my working life as a copy and commissioning editor of sundry ‘dev. ed.’ publications aimed at farmers and growers in the UK and in francophone and anglophone Africa.

Finally, I’m not normally given to talking about stuff like ‘pride’, but I do think that it should not pass unremarked that UEA – from its modest, unpretentious beginnings – spawned two pioneering Schools – Environmental Sciences and Development Studies – which in the fullness of time turned out to be ‘right on the money’ and have become global centres of excellence in their respective fields both in teaching and in research/professional activities. DEV and ENV were far-sighted. Both have accomplished so much. That’s something to celebrate. And to be proud of.

Martin Wallis

Norwich

May 2023

Leave a Reply